Language

School of Choctaw Language

CHOCTAW GREETINGS AND SALUTATIONS

When people speak the Choctaw language, it preserves, promotes and protects Choctaw culture and sovereignty. Watch this video to learn all the ways to say “hello” and “goodbye” in Choctaw.

Choctaw Nation Film Festival

The Choctaw Language Department invites high school students to participate in a film competition. Winners will be announced during the Princess Pageant at the Annual Labor Day Festival.

Common Phrases

halito

hah-lih-toh

hello

yakoke

yoh-koh-keh

thank you

chi pisa la chike

che pe-hn-sa la che-keh

until we meet again, see you later

Choctaw Lesson: Chahta Anumpa

This scenario highlights what to expect when visiting the Choctaw Cultural Center.

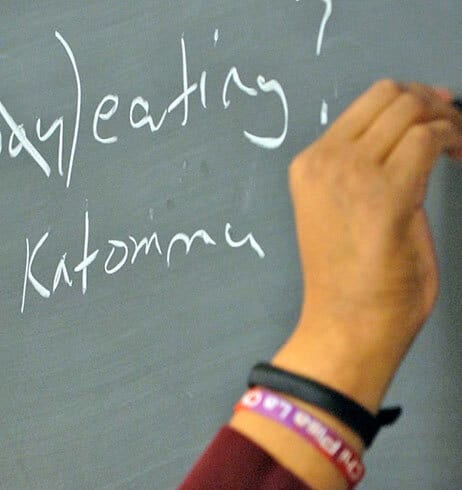

CHOCTAW LANGUAGE CLASSES

Find in-person and virtual classes that fit your schedule. Sign up today!

See More

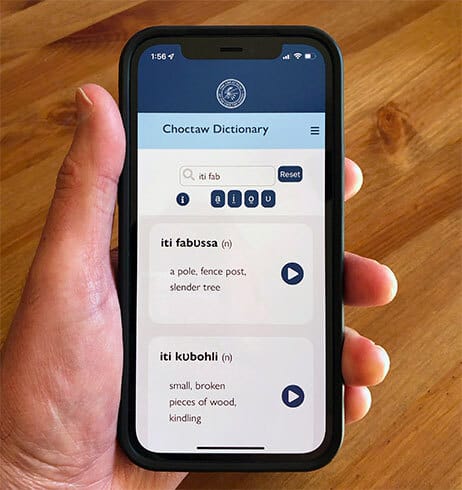

Choctaw I

Learn the Choctaw language through comprehensive lessons, downloadable resources and audio clips. Begin your journey with the first module.

See moreChoctaw II

Continue your Choctaw language learning journey with the second module using comprehensive lessons, downloadable resources and audio clips.

See more